Moving on to part 2 of our mini-series covering the many sources of economic rent. Our next class of non-reproducibles that generate unearned payments for their owners are non-renewable natural resources. These resources are included in the Classical economic definition for “land,” but they’ve evolved to receive their own special treatment in terms of taxation. Let’s dive into why.

The Bounty of Nature

The Earth, through our species’ time on this planet, has provided plenty of resources with which we can produce and provide the goods and services we need to one another. Of course, land is the biggest example, as we do and make everything on it.

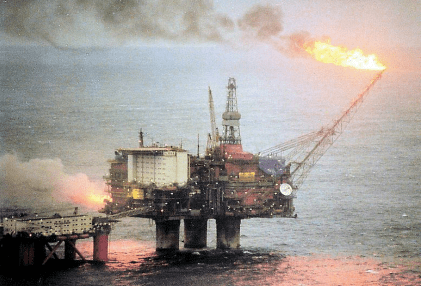

But there’s more to nature’s bounty than just the ground we stand on. Beneath the ground, there exist resources we make extensive use of as well. By far the most famous example is oil, as it’s the primary way we fuel our lifestyles: driving our cars, cooking our food, flying our planes, etc.

This hasn’t come without tradeoffs. There are definite problems with how these resources are used, like the burning of oil and the pollution it creates. The environment as a whole is non-reproducible by humanity, so destroying it through air or water pollution can, in a sense, be seen as a form of economic rent.

However, that’ll be covered in a later part. What matters here is that subsoil minerals and other extractable resources are necessary for production and highly desirable in their own right, but the deposits they come from are non-reproducible.

The Great Underground Robbery

The potential economic rent obtained from controlling deposits of non-renewable natural resources and the right to extract them are enormous. The sheer amount of unearned wealth that can be extracted off those who rely on those resources to survive, which is almost all of us, has given rise to massive issues and a dedicated need for care in how deposits of non-renewables are handled.

Unfortunately, in many cases, these rents have often been left to private deposit monopolists to turn into vast, undeserved fortunes and brutal conditions for the locals they use in their operations. Even worse, locals whose jurisdiction includes these deposits are paid no compensation for when they’re taken exclusively, leaving them with nothing.

Take, for example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The DRC is the wealthiest country on Earth in terms of its mineral wealth, with an estimated underground value of about 24 trillion dollars. But in cruel contrast, the country only collects a small portion of its natural resource wealth, about $13 per Congolese citizen as of 2010. In turn, the Congolese are some of the poorest on Earth, with about three-fourths of the country surviving on just $2.15 or less a day.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is currently undergoing what is known as the Resource Curse. The resource curse is a term referring to the seemingly inverse relationship between natural resource abundance and true produced wealth, where the more natural resources a country has, the poorer off its citizens tend to be.

Poverty isn’t the only effect of the Resource Curse. Corruption and wars (including an ongoing one in the Congo’s northeast, also owing to natural resources) are further effects as well.

Needless to say, how natural resources are treated is incredibly important to the well-being of the economy. It can either be the path to prosperity or poverty, depending on where its value goes.

If you’re familiar with the Georgist movement, this sentiment might sound, well, familiar. Indeed, George dealt with this same problem as far back as the late 19th century, and as is the case with land, the Georgists have made their own answer to fix the problem of natural resources and the Resource Curse.

As it is with all other non-reproducible resources, the theory behind the Georgist solution to the resource curse in deposits of non-renewables is the same: let the economic rent for these deposits be taxed away and returned to the people in some way as a stand-in for taxes on production, and the benefits would be tremendous.

It seems simple enough—just tax the ownership of these mines and other non-renewable deposits. However, there is a significant fork in the road when it comes to Georgists dealing with taxing the ownership of these deposits for a special reason.

That reason being that these deposits, unlike the parcels of land we walk on, are depletable.

A Shift in the Georgist Gears?

The Georgist take on extractable natural resources is quite different from our views on land. The flagship policy proposal of Georgism, the Land Value Tax (LVT for short), taxes the ownership of land by its value based on the amount of time the current owner chooses to withhold it. This incentivizes owners of land to use land quickly according to how valuable their plot is, which is good.

But for deposits of non-renewable resources, fast-tracking their extraction has been seen as being potentially problematic, especially concerning premature extraction and future scarcity. The idea is that taxing based on time is efficient for permanent natural resources only, but it’s not as efficient for maintaining temporary natural resources, like deposits of non-renewables, for future generations.

So, what’s the solution to this? Well, the answer is simple. Rather than taxing these deposits based on how long they’re owned, tax them instead on the value that’s extracted from them, and make extractors pay for depleting a deposit by the value of the material taken from it.

The policy proposal to achieve this is called a severance tax. In a severance tax system, as stated above, the amount of revenue paid is based on the total value of raw material extracted from a deposit.

However, this has generated some controversy on whether we should tax based on time of ownership or at the time of extraction. Some Georgists have argued that taxing at the time of extraction (even if it doesn’t reduce the total amount of resources extracted) and deferring the rate of extraction is inoptimal compared to charging rent to extraction rights themselves. This is mainly a matter of personal preference.

Another argument against the severance tax is that severing natural resources is also the result of labor and investment, and so taxing it would be like taxing production. To offset this, the value of the actual economic rent itself can be derived from the cost of the total operation without including production, mainly though cost deductions given to businesses.

This is already being done by our real-life success story, where the cost of capital needed to extract non-renewables is taken out and only the rent is left for taxation. That real life success story, which turns out to be the one locality that has gone the farthest with severance taxation, is Norway.

A Real-Life Success Story: Norway

Norway’s history with oil is one of the most prosperous in modern history. Lars Doucet covers the story in great depth with his own article covering Norway’s oil fund, so this article will only cover a few aspects of it.

Norway’s story with oil started with a man by the name of Farouk al-Kasim. Al-Kasim, originally from Iraq, had recently moved with his family to the homeland of his wife Solfrid, Norway. It was the only option they had in order to find treatment for his son’s cerebral palsy.

With a background in oil, al-Kasim began looking for work he could do in his new country. Results wouldn’t take long, as shortly after his arrival, he helped the government of Norway successfully discover oil deposits within the country’s borders.

What was found was huge, as Norway held what has been equivalent to 7 billion barrels of oil as of 2023. The country was sitting on a fortune, but a massive question rose up above all the rest. How should Norway handle these new reserves and avoid the same fate befalling other oil-rich countries of the time?

To figure this out, al-Kasim had to look upon his past. He had a long background in oil, having worked with the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) on oil exploration and extraction projects in his home country of Iraq. However, the IPC was rife with problems, as it held an effective monopoly over projects related to oil extraction in Iraq, allowing it to be exploited by some of the largest oil companies in the world until 1961.

Another alternative al-Kasim had taken note of was nationalization of oil-related projects, which the government of Iraq eventually did in 1972. However, nationalization brought its own problems, as “publicizing” the IPC with government ownership didn’t remove its non-reproducible stranglehold over oil projects. Bureaucrats obtained special powers over Iraq and other countries engaged in nationalization akin to the large, rent-seeking oil companies of unfettered privatization.

Not wanting his new home to fall into the same fate as his old, al-Kasim immediately set out to make a plan that would give the Norwegian people the prosperity felt by the value of oil. In contrast to what Iraq had done, al-Kasim didn’t create a full monopoly over all oil projects in the country.

Instead, he only allowed some state ownership through Norway’s state-owned Equinor but immediately contrasted this by allowing international competition to come in and keep oil projects on their toes. Ensuring competition in extraction was already massive in preventing rent-seeking in the oil production process, but where the benefits boomed was in the Georgist policy he put in place afterwards.

Following the creation of Equinor and the preparation for extraction, Al-Kasim had the government implement a severance tax on the country’s oil. But what the Norwegian people got wasn’t just a tiny smidgen of the oil’s value (unlike most US states), what they got was a staggering 78% of the oil’s total value. At the same time, Norway allowed special deductions on taxes related to the capital necessary to perform the research and extraction relating to oil, spurring investment while capturing over three-fourths of the economic rent for the people.

In order to ensure this money would belong to the Norwegian people, the government invested the oil rents in a sovereign wealth fund. One that was designed to protect and provide for the people from economic woes. As of the making of this article, the fund is worth about 20.16 trillion Norwegian kroner, roughly equal to 1.8 trillion US dollars.

Across a population of about 5.6 million people, that’s roughly 321,000 US dollars per Norwegian, all already stored up as wealth. In contrast to the citizens of countries engaged in relentless privatization and nationalization, the Norwegian people have gotten the broad benefits of their natural resources.

Conclusion

Needless to say, severance taxation amidst a competitive environment for extraction is among the most optimal ways to get the value of non-reproducible deposits of non-renewables to the people.

The Resource Curse is powerful and deadly for any country that may face it. However, among the rush for natural resource extraction, there can be freedom. If Norway and its incredibly successful, effectively Georgist system teach us anything, it’s that allowing free competition in, and compensation for, the extraction of non-renewables is the key to prosperity.

Through taxing the severance of resources from the Earth they are found in, a Georgist system can pave the way for the people to feel the wealth they rightfully deserve from the natural resources bound to their homeland.

Leave a comment