AI is advancing at an exponential rate. The largest language models, which just a few years ago had billions of parameters, now scale into the trillions. And every hour, more data is generated than in entire centuries of human history, feeding ever-smarter systems that automate work, generate media, and reshape industries.

By the end of the decade, AI will be integrated into everything that uses electricity and internet, especially with imminent arrival Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). The only question left is not whether AI will transform society, but how prepared we are for what comes next.

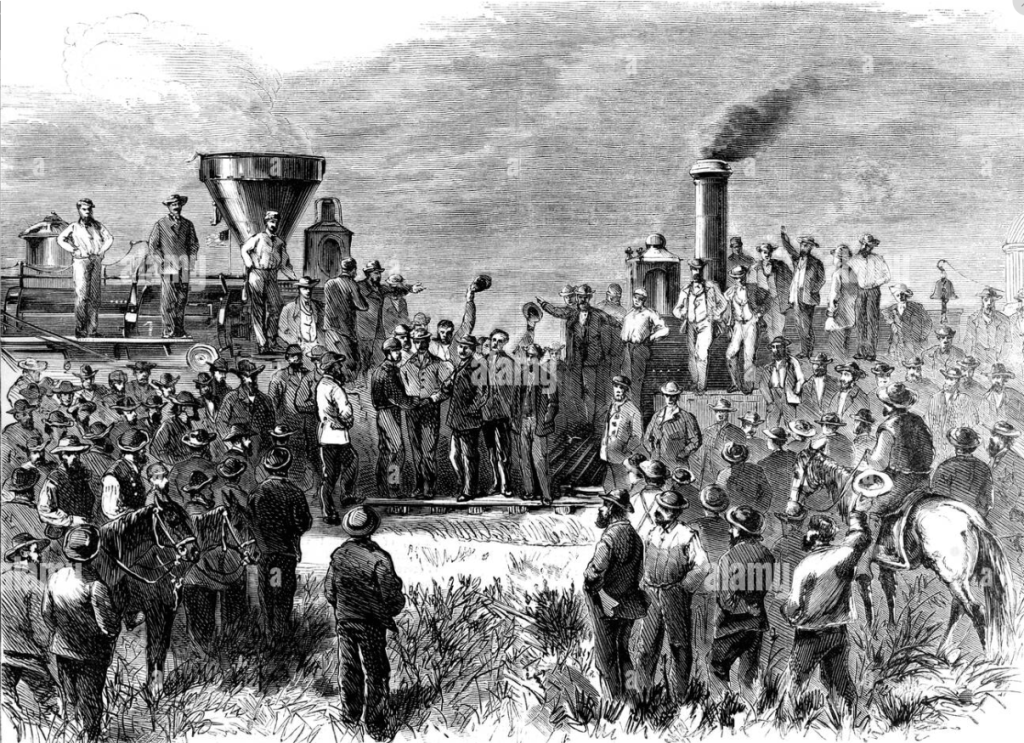

AI technological advancements, while on the surface appearing to be completely new and unchartered territory, are really part of a repeated historical cycle. Americans of the latter half of the 19th Century had to grapple with the effects of new technologies increasing the productivity of the economy while rendering old tech obsolete.

alamy.com

Henry George asked, “What is the railroad to do for us? — this railroad that we have looked for, hoped for, prayed for so long?” in his piece, What the Railroad Will Bring Us (1868), about the Transcontinental Railroad that was nearing completion.

Telegraph networks put Pony Express riders out of work. Stagecoach drivers, wheelwrights and ferrymen had their businesses permanently altered by the rise of the locomotive engine and steamboat. New steel mills and foundries made better use of iron ore than the town blacksmith shops ever could.

We have been anticipating the rise of machines and artificial intelligence for decades if not centuries. Science fiction as a genre seemed to begin as a means of predicting future technologies. Most people agree that new advances in technology that have a wide-reaching impact on economy and society should probably work for the public benefit.

If there must be machines and automation, it should be put toward societal benefit rather than solely the bank accounts of the investors and inventors (though an innovative society should ideally reward idea creation and risk-taking investments in new and useful projects).

As Henry George argued, improvements in infrastructure and advances in technology increase land values not because of individual effort, but because of the growth and cooperation of the whole community. The question is whether we let those gains be privatized or return them to the public that created them.

People anxious over the new wave of advanced language model AIs ask questions like: Will AI lead to mass unemployment? Will we need a basic income to survive? What jobs are safe from automation?

These questions represent legitimate concerns and fears of the future. Luddites have fought to prevent the mechanical takeover since the 1800s. I however think a better question to ask is: what is the robot to do for us?

I think fearing and fighting the development of technology has never worked. Everyone who resists a new technology is always left behind. Like avid newspaper readers who avoid the internet and music lovers who have convinced themselves that their scratched vinyl from 1978 sound better than the digital remasters online.

AI, like the railroad, is here to stay. AI is only the current frontier of the very old process of technological evolution. What should we be worried about then? While I am not an AI expert by any means, I think we should be more worried about the economic system these new technologies are born in.

Technology, in the economic sense, is also known as capital. In our capitalist system, the boundary lines of economic growth are set and re-set by new technologies. The same city, the same workers, the same businesses, with the same land and natural resources can produce exponentially more wealth if the right pieces of technology enter the equation.

And what exactly is technology and capital? Although the terms have been used in so many different ways to the point of almost removing their original economic meanings, capital and technology is the result that occurs when human labor and genius is applied to the physical material of the natural world.

This brings us back to that old idea of the three factors of production: land, labor and capital. All resources, including the very substance human bodies are made of, originate from the land, the sea, the skies, the Earth and really the entirety of the Cosmos.

The moment a human being exerts physical or mental energy onto these resources to “create” or recreate is when human activity and the economic system begins. The result is works of human labor: capital, technology, roads, cars, buildings, clothes, computers, Five-Piece KFC Bucket meals and everything humans have left their mark on in this world.

Economic booms and busts are often spurred by breakthroughs in technology. There was a boom and bust of speculative land values along the Transcontinental Railroad when it was being built, leading to the panic of 1873. The new technology of wireless internet led to the Dot Com Bubble crash, and of course the speculative bubbles happening right now with blockchain and AI.

All of these very different times in history and different technologies have one thing in common: the economic growth from a new technology was captured by the rentier class at the expense of the working many.

As usual, economic rent is the culprit behind inequality, financial crises and poverty. Make no mistake, the speculative bubbles around new technologies are just various forms of rent-seeking, or the extraction of wealth without contributing anything of value, neither labor nor capital.

Marxists say the owners of capital are extracting unearned income from labor, but we Georgists say that the rent seeking owners of monopoly resources extracts from both the laborer and the provider of capital.

Capital is the physical material we need for the production process, it’s the tech that workers use to be more productive. Returns on productive tech and capital do not cause the speculative bubbles and recessions that the owners of financial assets such as land titles, stocks and debt obligations do.

Financial bubbles bursting often causes industrial recessions with 2008 as a glaring example. The upper class, some 10% of Americans, who control the most wealth take massive chunks of ownership of new technology patents, stocks, debt obligations and land titles during the “good” times when asset prices are rising.

Then, as soon as asset prices reach unrealistically high levels, the boom turns into a bust and the assets that are now falling in price are dumped onto the wider market and public, with the rentier class laughing all the way to the bank.

Buying land next to the railroad was a good idea in 1868, a terrible idea in 1873. Same with website domains, patents and any other speculative assets when their bubbles burst.

Yes, prices can recover after crashes, but aren’t we all sick of the boom-and-bust merry-go-round that leaves the poor poorer and the rich richer every time?

The economic benefits of AI are being increasingly captured by a small group of tech monopolists. AI-driven automation threatens jobs, but the bigger issue is who owns the profits generated by AI. Without smart taxation, AI will exacerbate wealth inequality, just as past technological revolutions did.

Just as George argued for a Land Value Tax to prevent land and railroad monopolists from hoarding wealth, we need similar policies to counter AI monopolies. A tax on intellectual property and patents, for example, could prevent excessive AI rents and redistribute wealth more fairly.

I should mention that Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, has acknowledged the relevance of LVT in his blog as well as in an article for Time magazine.

Altman argues that while AI will generate immense wealth, without proper redistribution, most people will be left worse off. He proposes a taxation system focused on capital, specifically, companies and land, to fund an “American Equity Fund” that would distribute wealth more fairly.

While his program is a good step in the right direction, Altman may not know that the point of the land tax is not to target capital or corporations, but to prevent monopolies. Altman is already working on monopolizing his company’s technology, and fellow tech monopolist Elon Musk is both correct and hypocritical in his anti-trust lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI.

If AI leads to widespread job displacement, ideas like a universal basic income (UBI) could help stabilize the economy. The revenue from LVT and an intellectual property tax could fund a citizen’s dividend, ensuring that AI benefits everyone, not just a handful of corporations.

Henry George was known as “the Prophet of San Francisco” because of his predictions on the booming growth of the city during America’s move West in the latter half of the 1800s. Now the economic growth is in Silicon Valley.

AI presents both economic opportunities and threats. How we respond will determine whether it benefits the many or the few. Henry George’s insights remain as relevant as ever: economic progress should not lead to private monopolization of wealth.

To ensure AI serves humanity rather than enriching monopolists, we need Georgist policies like LVT and IP taxation to share the gains of technological progress. An economic system where land and labor are prioritized over capital is one that has no need to fear unemployment or environmental degradation from emerging technologies.

Epilogue

I normally would end the article at this point but have added an epilogue to answer an important question on my mind: How can we know if a new technology (or inventor) is evil or good? We may know them by their fruits.

“Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravenous wolves. You will know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes from thornbushes or figs from thistles? Even so, every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Therefore, by their fruits you will know them.” (Matthew 7:15)

The question is, does this technological advancement or scientific discovery reach for the Omega point of Christ? Setting Christ as the end point of technology and scientific progress is a synthesis of the moral and the practical. I understand non-Christians will have a harder time with this concept if I don’t explain what I mean.

Let me briefly appeal on the grounds of logical reasoning, specifically the transitive property of mathematics: If a = b, and b = c, then a = c.

If Christ (a) embodies the totality of Truth and represents the final goal of human perfection (b), and science and technology (c) seeks to find truth and achieve human perfection (b), then science and technology (c) is, whether knowingly or not, striving toward Christ (a).

Scientists and technologists are looking for the holy grail. Maybe not the exact wine cup of Jesus of Nazareth (although the archeological establishment would probably like to find that), but science and technology strives for the perfect thing.

Scientists everywhere would hang up their lab coats today if anyone in their field discovered the true “philosopher’s stone” or if the resurrected Jesus manifested before their eyes like when Paul of Tarsus was blinded on Damascus Road.

The search for ultimate Truth, whether in physics, medicine, AGI, or philosophy, is, at its core, a search for Christ. The only question is whether we recognize Him when we find Him.

Christ represents everything the scientific community of every field dreams of achieving: eternal life, the curing of diseases and ailments, the perfectly planned city, world peace, full knowledge of the cosmos, the power to move mountains, the perfect solution to every problem.

If Christians call these things the parts that make up Christ, and the scientists are looking for all of these same things, then the scientists are looking for the Christian definition of Christ.

Every religion on Earth is also deeply interested in the utopian ideals that make up the definition of Christ, though they have thousands of different words and books to describe the indescribable.

This concept in theology is known as the “eschaton” or the last thing to ever exist. Science and religion have eschatons with different names.

Modern scientific institutions all came from the church. Yes, church leaders at many times in history have obstructed scientific progress and even executed great scientific minds, but the yearning to know what is beyond the veil of our daily lives is in science and religion both.

The best technologies are the ones that keep Christ’s commandments. If we love Him then we would keep his commandments. Technology must feed the hungry, clothe the naked, heal the sick, give sight to the blind and repair the crippled.

“Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.’

“Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?’

“The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’ (Matthew 25:34)

It’s not blasphemy to use technology to imitate Christ’s miracles: “Very truly I tell you, whoever believes in me will do the works I have been doing, and they will do even greater things than these, because I am going to the Father.” (John 14:12, NIV).

The Son of Man is the new humanity, a new breed and the end point of our evolution. We know a tree by its fruits. Technology that perpetuates sin, technology that doesn’t keep Christ’s commandments and technology that does not manifest the work of Jesus is technology used for evil and must be resisted.

We should remember governments and economies are technologies of a sort. A government can be programmed and re-programmed with every new administration, constitution, or regime. Economic systems, too, are often structured by the taxation and money-issuing policies of the government.

Dominic Frisby, British economic comedian and author of Daylight Robbery: How Tax Shaped Our Past and Will Change Our Future, wrote: “You design a society by the way you tax it. You determine a society’s destiny – whether its people will be prosperous or poor, free or subordinated, happy or suppressed, inventive or censored – by the way you tax. Taxation is the operating system.”

Henry George described his vision of the Single Tax Land Reform in America as a religious revelation. Without having to speculate on George’s personal religious beliefs, we know he was a true social scientist.

He could see an intelligent economic system that alleviated poverty, empowered the workers and granted the free gifts of the Earth’s wealth to all. His scientific study of political economy fueled his religious fervor for economic justice. He could envision a more Christlike and humane society and government system that guided his work as a land reformer and public intellectual.

Human technology needs the guiding star of Christ (eternal and perfect human love) or it evolves in crooked and lost ways. Science and technology, and really all works of man, with a moral compass facing True North, can make Heaven on Earth.

Leave a comment