And How a Forgotten Economist’s Ideas Can Help Fix It

Introduction

Farming is perhaps the most important, and among the longest-lasting, professions in human history. We cannot survive without food, so regardless of how different our jobs may be from the rural lifestyle, we all rely on the subset of our population who dedicate their hard work and labor to producing and providing us with the sustenance we need for survival.

Unfortunately, despite just how valuable farmers are to everything we do, they’re currently undergoing a crisis of unaffordability. The returns to crop-growing for many farmers isn’t enough to catch up to their cost, and it’s throwing those swept under the tide out of work.

So, what’s the reason for this? To get down to the bottom of this, I’ll be covering 5 different problems, heads of the proverbial hydra, that push farmers into poverty and will explain how the ideas of a forgotten 19th century economist can heavily reduce, if not outright fix them all.

So, without further ado, let’s fight the five-headed hydra head-on.

The First Head: Taxes on the Farmer’s Hard Work

One of the biggest burdens people of all walks of life have to face is taxation. We pay taxes for public services, of course, but those taxes we currently levy are on both our work and investment. These taxes force us as a society to forgo producing and providing as many goods and services as we would otherwise want to make and raise prices to offset the higher costs caused by tax burdens. Farmers are no different.

Last month, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released an article detailing that most of the tax burden levied against farms, at least on a federal level, falls on the income of their production. This isn’t the only tax levied against a farmer’s hard work, though. Self-employment taxes, Social Security taxes, and taxes on a farmer’s improvements to their land are additional burdens they must pay.

All of these taxes cut into the incredibly important earnings farmers get from their labor and investment into their craft, pushing up the cost of production and making it more difficult for farmers to pay off their costs.

A more recent and just as relevant topic in this discussion is heavy trade barriers in the form of tariffs. American farmers make direct use of imports, such as Canadian potash in fertilizers, to grow crops. This is the same potash that our current president, Donald Trump, would target in his plans for a 25% tariff against Canada, among other nations. If potash becomes more expensive for farmers to import, the impact would be tremendously harmful, blindsiding them by heavily increasing the costs required to feed their crops.

Needless to say, taxes on production and trade directly push down working farmers while heavily increasing the price of food. It’s an inefficient and harmful way to raise public revenue and, as we’ll see later, is a poor choice compared to taxes that can actually benefit farmers.

The Second Head: Land Profiteering

There’s a simple truth that underpins the problem with land: it’s necessary for life but non-reproducible. We can’t make more of it (not even reclamation makes more actual land), and we can’t take plots of land of specific qualities and bring them to plots without those qualities. What we’ve been given is what we’re forced to take.

This means one very important thing for everybody, including farmers: the only choice we have to access a specific plot of land we desire is by buying or renting it from whoever owns that plot already. Since nobody can make more of those specific plots to increase supply and lower prices, whoever owns the specific land we want can charge the excluded as much as they’re willing to pay, without any fear of competition to give a cheaper option.

Land profits, when left unchecked, can be incredibly problematic. One way is by inviting land speculation, where someone buys a piece of land not to use it but to profit off its increase in value.

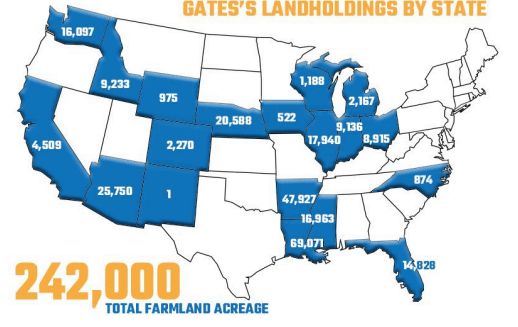

For example, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos own hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland each, making it more scarce than it needs to be and driving up prices further. The unaffordability this creates for farms makes it much more difficult for non-landowners to access their own land to farm, as much of it is already owned by some investor not making any use of it.

Another major problem is land concentration. The late economist Mason Gaffney detailed the impacts of falling tax rates on land, and in turn its increased profitability, on trends within the agricultural sphere.

As he puts it:

“Lower farm property taxes are associated with lower ratios of capital to land, and labor to land, both overtime and among states. They are also associated with larger mean farm size and less equal distribution of farm sizes.”

(Just a quick note, even though Gaffney uses property taxes, he’s only doing so because it’s the only tax that collects the value of land directly. An ideal tax would only go after the land and leave the buildings untouched, which I’ll talk about later.)

Unchecked profits in the land are a struggle for working farmers. They allow already established landowners to continue growing their power at the cost of the working farmer’s prosperity. Many of these landowners, like the Mormon Church, hide under a veil of farming in order to profit off increased land prices. It’s one of the biggest problems holding down workers and actually productive capitalists in all sectors, and farming is a glaring example of it.

Where Do the Subsidies Go?

This is just a quick sidenote, but a corollary of land being non-reproducible is that farming subsidies, originally designated to help working farmers, actually result in higher land prices.

As we discussed earlier, benefits already established landowners at the cost of truly working farmers. So long as subsidies continue to be given out while land is left for profit, a policy originally designed to help working farmers ends up becoming a spin cycle crushing them, pushing the big up and keeping the small down.

The Third Head: Patent Monopolists

“Monsanto is the Devil” is a term I’ve heard frequently when it comes to the farming lifestyle. Why is this the case? Well, the reason is simple, Monsanto uses their position as one of the foremost seed patenters to extort farmers.

Along with other farm patent giants like DuPont, Monsanto and the like have been responsible for using IP to make many beneficial farming innovations non-reproducible by the working farmers themselves, primarily in the form of seed patents.

The seed patents these large patent monopolists own effectively ensure that nobody can reproduce the sale or use of those patented seeds if it’s not within the watchful eye of these big agribusiness monopolists. And if they try, they’ll be shut down legally.

In turn, seed giants have gained the power to charge farmers tremendously high prices for the very seeds humanity needs to survive. For farmers, there is simply no other option to feed the Earth than to accept the extractive deals these companies lay out, giving them the power to push those reliant on planting these seeds into a monetary pit with few to no strings attached for their patent privilege.

The Fourth Head: Pollution

Thus far, we have seen two massive barriers to farmers even being able to begin the planting process: obtaining land at high prices from landowners and obtaining seeds at high prices from seed patent monopolists.

But then comes the actual yields themselves and the difficulties associated with them: planting the seeds, getting them nutrients, harvesting the crops, and more.

One of the big threats to a farmer’s yield, which is also outside their control, is pollution. Pollutants in both the air and the water have been directly linked to poorer yields and plant death, cutting into the revenue farmers could have earned for all their hard work.

Pollution’s effects are not just limited to the degradation of the air and the water. They also include climate change, which further reduces farmers’ yields. Decreasing revenue and limiting the ability to feed the planet spells extreme trouble for people’s health across the world.

Many working farmers have already started taking note and adapting to fight the effects of climate change in order to keep the world fed. However, without a way to require direct compensation from polluters who release incredibly high amounts of pollutants into the environment, the damage caused to crop yields will continue to worsen.

The Fifth Head: Denial of the Right to Repair

Every tool needs repair. It is a simple fact of life that nothing people make lasts forever. The same goes for farming: tractors, harvesters, and other tools must be repaired when used constantly and strenuously. Unfortunately, like other steps of the farming process that we have already discussed, the repair process is also unnecessarily harmful to farmers.

The final head of the hydra to dwell on is the right to repair, or more specifically, the lack thereof. In a way that is somewhat similar to big agribusiness’ seed patents, major farm manufacturers make the right to repair farming tools non reproducible by anyone other than themselves. This allows them to extract around four billion dollars annually from farmers just by owning that exclusive repair right.

As I’ve probably drilled into your head by this point, this is just another one of the many extractive wrenches in the farming process that push farmers into unnecessary levels of poverty and hardship.

Henry George’s Solution

As we can see, there’s a whole slew of problems that farmers are forced to face, not through any difficulty in the farming industry itself, but because of how our system operates.

The problems I have laid out here may seem like they’re only getting relevant in the modern era, but they aren’t actually anything new. They were also present during the Gilded Age, a time of great strides in technology matched with great troubles with poverty for the common American that stretched from around the 1870s to the 1890s.

One of the figures who rose out of the Gilded Age to fight for socio-economic progress for the common man was a now mostly forgotten economist by the name of Henry George. Having been a victim of the widespread poverty seen during the Gilded Age himself, George set out to find the answer to the reason why technological improvements weren’t benefitting everybody.

Eventually, George found that it was the backwardness of what streams of income our system chooses to tax and publicize or leave untaxed and privatized. The best way I could describe it is that:

In our current system, any time people use new technological advances to produce and provide goods and services for others, they’re taxed for it by the government. In contrast, whoever owns the resources needed for that production, but are non-reproducible, can use new advances as an excuse to charge a higher cost to those excluded. The profits from exclusion allow them to hoard and misuse these resources while paying little to nothing in compensation.

This income, identified by economists as being extracted by controlling non-reproducible resources, is called economic rent.

The five heads of the hydra we discussed above all stem from the fundamental problem George found in the economy. The first head, harmful taxes on the work of farmers, combines with the remaining four heads, various forms of privatized profits in various non-reproducible natural resources and legal privileges, to push working farmers deep into the trenches of poverty and unaffordability.

Many policies we’ve already utilized to try and help farmers have been band-aids. Farm subsidies, perhaps the biggest example, don’t help farmers much when they turn into higher land prices. Preventing mergers and acquisitions of owners of seed patents won’t fix the problems of the patents themselves forcing high seed prices.

As we all know from the story of Hercules, cutting heads off the hydra only results in them growing back.

Instead, George went after the root causes that he felt were causing poverty among progress. After some deep digging, George found a solution. As I would describe it in my own words:

Tax (or dismantle) the income people extract from controlling what is non-reproducible, and use the proceeds to end taxes on what the people produce.

Simple. In line with this fundamental philosophy, supporters of Henry George’s philosophy (known mainly as Georgists) have supported solutions to each of the 5 problems outlined above.

So, let’s find ways to cauterize the heads of the hydra.

Georgist Solutions

- Harmful Taxation:

The Georgist solution to harmful taxation is to simply remove them (as much as possible) in favor of better forms of taxation. Income taxes, sales taxes, taxes on farm buildings, or tariffs on what farmers have to import. Georgists want to reduce these harmful forms of taxation as much as possible.

While it may seem like a massive loss in public revenue across all of society to get rid of these forms of taxation, some of the solutions to the next few problems should cover the revenue in a way that increases efficiency while decreasing inequality. - Unaffordable Land:

The Georgist solution to the problem of unaffordably high land prices is simple, tax those prices through a Land Value Tax (or LVT for short).

The LVT is, as the name suggests, a tax that targets the value of land. Land values are typically assessed by looking at market prices for a specific piece of real estate and separating the land and building portion.

By taxing the value of land, an LVT reduces upfront land prices and instead turns them into a rolling tax on landowners. This doesn’t mean the tax base for land has been reduced, the annual income someone can get by renting out a specific plot (known as land rent) is the same, it just changes who’s getting it, from the landowner to the public.

The effects of a LVT are a direct counter to the harmful impacts of land speculation and concentration. By turning the extra income from withholding land into a burden, an LVT would make speculation tremendously unprofitable and force once withheld land to be put on the market, making that land more accessible for farmers. Removing land speculation would drop land prices by making usable land more readily available and cheaper, heavily reducing the barrier of entry for farmers.

As it relates to concentration, shifting taxation onto land would cause the most land-efficient farms to have the lowest relative tax burden. Small, working farms are more land efficient than big farms and, of course, infinitely more productive than land bankers, allowing the former to prosper and making the latter pay a far higher relative burden. You might be worried that landowning working farmers would have a high LVT since they use a ton of land. Thankfully it’s not an issue, as the tax burden imposed on rural land would be quite low. Most of the burden imposed by a land value tax would be placed on urban land, leaving a low burden for rural land that can be paid off well by farming, especially small farms as discussed earlier. At the same time, if you’re a renting farmer who either works for a corporation or some landlord, you won’t have to worry much about your landlord trying to pass the tax on. Due to a combination of landlords already charging as much as they can get out of non-landowners, and the fact that reducing speculation would make land far more readily available, rural landlords would end up eating the tax without being able to pass it on. So, the idea is clear: tax the unearned profits associated with the land and reward those who work it, while forcing those who hoard it to either work it or give it to someone who will. Breaking the land barrier would be an astronomical gain for farmers, but there are still other problems which need to be solved. - Patent Monopolists:

Georgists have called for IP reform as far back as the days of Henry George himself, when he criticized patents in 1888. Around 140 years later, this sentiment has remained the same. I’ve already covered the Georgist critique of IP in a previous article, and all the issues with monopolization it creates. But to spare you the read (since we already talked about seed patent monopolists) I’ll skip ahead and give you the two primary solutions Georgists propose.

There isn’t a consensus on how we should handle IP in a Georgist system, but there are two avenues Georgists often take: Either replace our patent system with a prize system, or implement a tax on patents.

The extractive income gained by making beneficial innovations non-reproducible should not go freely to whoever owns the patent. Instead, innovators should either not have that exclusive right or should pay much of that income back to society. - Excessive Pollution:

The Georgist solution to reduce pollution is quite similar to the land. Seeing as how the natural world is non-reproducible, anyone who damages it by emitting pollutants should be expected to pay compensation through taxation.

Taxing pollution and requiring polluters to pay would increase their costs quite a bit, which would encourage them to find more environmentally efficient ways of producing and providing goods and services.

By stifling, if not removing the hugely negative impact of pollution, being able to use higher-quality air and water leads to better crop yields, allowing working farmers to produce and sell a higher supply of food while reducing their risks. Another note to consider is pollution within the farming industry itself, where current monocultural practices have caused damage to the environment, among other issues like the release of methane by cows. Thankfully, working farmers have given much care and attention to fighting pollution within the farming industry, as concepts like regenerative agriculture and reducing air pollution are becoming popular within farming. - Denial of the Right to Repair:

The right to repair for farmers has already been discussed pretty heavily in non-Georgist circles, so there isn’t too much to say here, but Georgists (from what I’ve seen) almost universally support the campaign for farmers to have the right to repair their own vehicles or choose which provider they want, instead of having to answer to some owner of a special privilege. Henry George himself called for the abolition of most special privileges, and the privilege of making the right to repair non-reproducible is no different.

Conclusion

So, there it is, these 5 major issues play a heavy factor in causing our current agricultural squeeze, to which Georgists support a solution. The problems laid out here aren’t the end of what farmers have to face, but reforming the system into one without them can massively improve the working farmer’s well-being.

Unfortunately, our current system allows the 5 extractive problems mentioned in this article to keep crushing the energy and reward of hard-working farmers. As time moves forth and these issues become more dire to focus on, looking back on the words of Henry George will be necessary to navigate the coming rough tides, hopefully allowing us to find calmer seas to set the farming lifestyle on.

Leave a comment