“It is at once evident, that rent is the effect of a monopoly; though the monopoly is a natural one, which may be regulated, which may even be held as a trust for the community generally, but which cannot be prevented from existing. The reason why landowners are able to require rent for their land, is that it is a commodity which many want, and which no one can obtain but from them. If all the land of the country belonged to one person, he could fix the rent at his pleasure. The whole people would be dependent on his will for the necessaries of life, and he might make what conditions he chose… A thing which is limited in quantity, even though its possessors do not act in concert, is still a monopolized article.”

“On Rent”, John Stuart Mill, 1848

There is perhaps no better explanation for why land and its returns, a subset of what is known as economic rent, is so unique than the above words of John Stuart Mill. Land is non-reproducible and purely limited in supply, the only way we as a society can access a particular plot of land is to buy it from that plot’s current landowner, nobody can reproduce it to provide at cheaper prices.

With nobody to compete in providing that plot of land, its landowner gets the power to charge society as much as they can afford to give, without the landowner having to provide anything in return.

The founding fathers of free market economic thought: Classical Liberal figures like Adam Smith and David Ricardo; as well as the later giants of economics they inspired, perhaps most famously Henry George, all recognized that the income of land was the income of a monopoly; it stood in contrast to the rewards of anything produced and provided in a competitive environment by workers or owners of capital.

Adam Smith makes mention of this in his pivotal and most popular work, The Wealth of Nations:

“The rent of land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give.”

Henry George would go on to become the single most famous advocate for taxing the value of land, heavily inspired by the writings of Smith and Ricardo. However, he, and even Adam Smith, weren’t the first to advocate for a market made truly free with a tax on the income of land.

Physiocracy

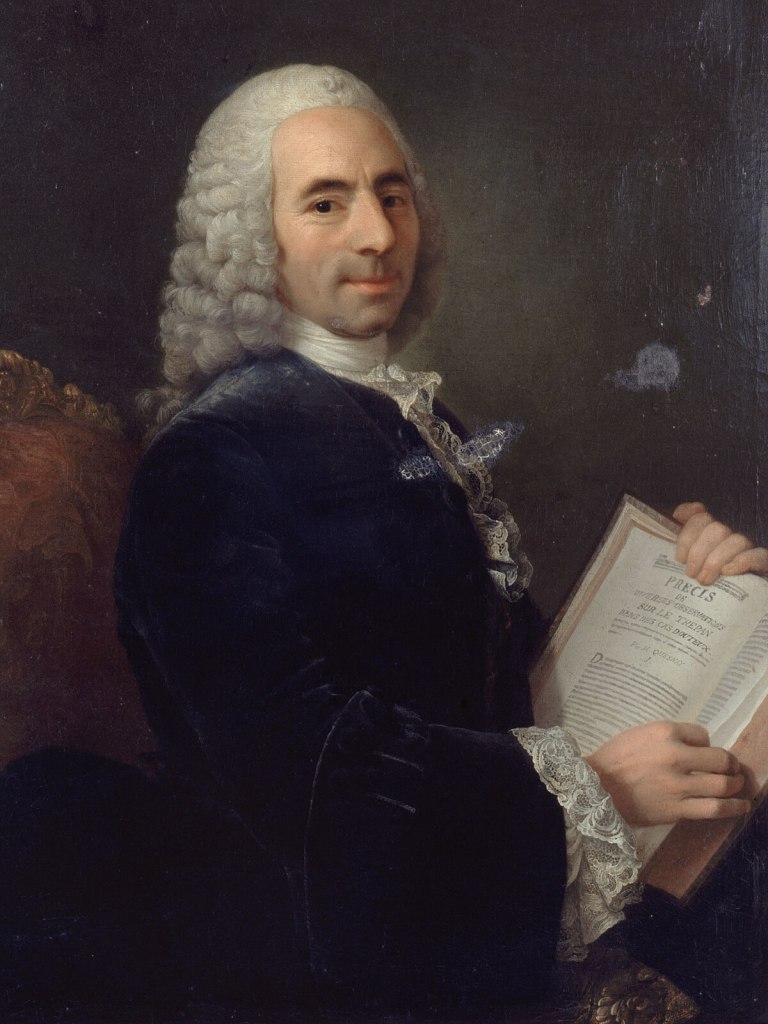

The first major group of free market advocates to call for the taxation of land value were the Physiocrats, a group of French economists who flourished in the mid to late 18th century. Some of their most famous members were Francois Quesnay and Pierre Samuel du Pont, the latter of whom shared correspondence with both Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

They referred to their tax on the landowner’s income as the Impôt unique, designed to replace all other taxes levied by the government. The Physiocrats recognized that taxes on the returns to land itself wouldn’t hamper production in the way other taxes would. They expanded this argument to advocate for free trade and the unhampered production and trade of goods and services.

This sentiment of the uniqueness of land as a tax base has been all but confirmed by modern economic thought. In the words of Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz:

“One of the general principles of taxation is that one should tax factors that are inelastic in supply, since there are no adverse supply side effects. Land does not disappear when it is taxed. Henry George, a great progressive of the late nineteenth century, argued, partly on this basis, for a land tax.

…

But it is not just land that faces a low elasticity of supply. It is the case for other depletable natural resources. Subsidies might encourage the early discovery of a resource, but they do not increase the supply of the resource; instead, that is largely a matter of nature. That is why it also makes sense to tax natural resource rents, from an efficiency point of view, at as close to 100 percent as possible.”

But, just how relevant are the rents of land and nature? The Physiocrats, Adam Smith, and David Ricardo were writing during a time before the Industrial Revolution, when agriculture and high amounts of land use were dominant. Now in our hi-tech economy, do those words still carry the same weight?

The answer is yes, in fact those words are more important than ever before. As we as a species have found ways to generate more wealth using less of land and other resources in inelastic supply, all that has simply led to those inelastic resources becoming far more valuable. Land, water, the electromagnetic spectrum, rare earth minerals, and more.

As an in-depth example, let’s take a look at one of the cradles of technological progress, Silicon Valley.

Silicon Valley’s housing strain

Silicon Valley shows us that land has gotten more valuable and more relevant as time has gone on, as seen in their housing prices:

Per this interactive map from the American Enterprise Institute, in 2023, land prices comprised about 75% of the overall prices of these houses.

A similar story can be seen in the United Kingdom, where land values have gone from a third to two-thirds of housing prices from 1957 to 2015.

The value of land has increased multiples over the past few centuries, while keeping its core role in the livelihoods of all. The progenitors of our market economy couldn’t have seen the path of progress we’d take, but the fundamental importance of land they saw has remained far after their time.

Truly Freeing the Market

The keys to a true free market were given to us by the group who served as one of its foremost thinkers, the Physiocrats. Their line of thinking was then passed through Smith, Ricardo, Mill, and most prominently, George. The Georgists who’ve followed Henry George’s depiction of the original Physiocratic message have gone on to apply this key to other resources which, like land, are fixed in supply.

Monopolies which corrupt the integrity of our market economy abound when allowed to profit from exclusively owning or using natural resources and limited legal privileges without payment. Add on heavy burdens placed on the trade and production that keeps the free market churning, and the market suddenly becomes very unfree and very monopolized. The key each person should know of when it comes to a true free market is this:

Stop taxing the value of things people produce, and instead recoup (or reform) the value of things that are non-reproducible

Simple, our market needs to rid itself of harmful taxation and the seeking out of economic rents that accrues to valuable, yet non-reproducible assets in order to become truly free as its most ardent advocates asked for. Tax the value of natural resources, and either tax or abolish limited legal privileges depending on what is preferred, then use any proceeds collected to untax work and investment.

Land remains far and away the most important of these assets, and remains among the highest barriers of entry to a generation of people and businesses trapped under the rubble of high land prices and rents.

Around three and a half centuries ago the first steps of true free trade were taken in the hopes of unlocking economic potential with the key mentioned above. Three and a half centuries later, and it’s slipped from our hands, waiting to be found and enacted by those who recognize the fundamental distinction between production and monopoly.

Leave a comment