The topic of whether a country should adopt free trade or protectionism has been a source of controversy for centuries. The pendulum has swung back and forth; be it the criticisms of the anti-free trade Corn Laws by classical economists like David Ricardo in the early 19th century, to criticisms of free trade by the 47th President of the United States, Donald Trump, who has gone on to implement high-rate tariffs against major trading partners.

With such a contentious issue making its rounds in the world news, some major questions come to the forefront: What are the point of tariffs, and what are the impacts of implementing them?

The Idea

Most simply, tariffs are a tax levied on domestic residents when they attempt to import goods from foreign producers. As an example to the large cost added to foreign imports by a tariff, if a country has a 20% tariff on steel, and a domestic company attempts to import 5,000 dollars worth of steel from a foreign country, that same domestic producer will have to pay an additional 1,000 in taxes to the government, bringing the total cost of the import to 6,000.

Tariffs are designed to prevent foreign goods from entering the country. By closing off access to outside markets, the only option for locals is to buy from local businesses.

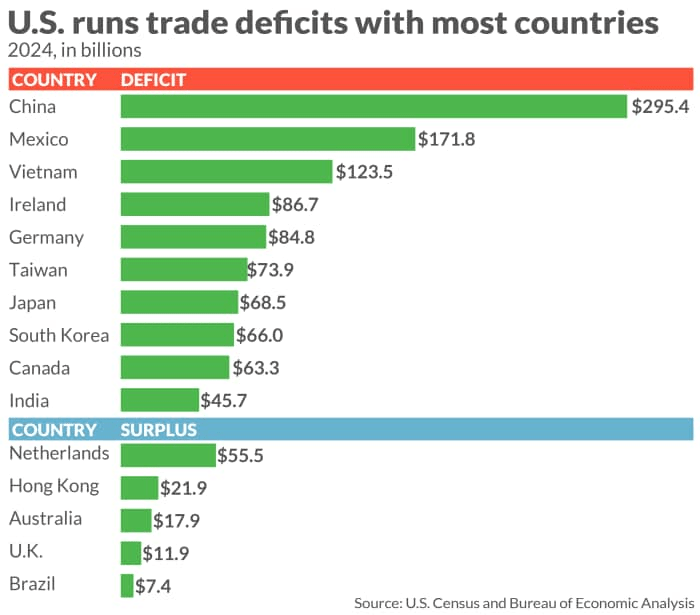

There have been several justifications given for closing off access to foreign markets by enacting tariff legislation. Among them are the protection of fledgling industries from more equipped competition to give them time to develop. Another one, particularly used by Trump in the justifications and calculations for his universal tariff, is the elimination of trade deficits.

Trade deficits occur when a particular country imports more from another country than it exports to that other country. Issues like protecting domestic industries and eliminating trade deficits sound important upfront, but there are massive gaps in the theory behind these justifications. For Trump’s in particular, trade deficits are not inherently bad for the economy. As we’ll soon see, it’s more problematic to try and stifle Americans importing more than they export, compared to letting citizens go about their trade freely.

The Problems

While there are certain cases in international trade that require more attention and care to deal with; e.g. direct war or slave labor, they will not be the focus of this article. Broadly speaking, tariffs are a particularly destructive way to do protectionism, and a destructive way to work an economy.

It is no coincidence that the Gilded Age, a time of great strife and great poverty caused by a great onset of monopolies and trusts, coincided with a time of incredibly high tariffs. Trump himself pointed to it as another justification for his high tariff plans, but it was a heavily misplaced one.

Going back to the fundamental point of tariffs, to prevent foreign goods from entering the country, the result is a form of semi-monopoly for the businesses of that locality implementing them over the giving of goods and services to the people. There still exists domestic competition that can erode any wealth extracted through the tariff, that is, or so it may seem, unless there is also a way to deny domestic competition as well.

As it turns out, that is exactly what happens with the wealthy and powerful who already own resources and privileges which are non-reproducible by all, foreign and domestic competitors alike. Owners of land benefited heavily from the high food prices brought by the same Corn Laws mentioned at the start of this article, while more modern natural resource holders in steel manufacturers find power and profits in them as well.

Through the ownership of those non-reproducible resources, that aforementioned domestic competition becomes a near impossibility. In turn, protectionism, by blocking off foreign competition, lends a helping hand to the owners of these absolutely scarce assets in their power to extract wealth through exclusion.

The Gilded Age was a time of great misery that the current administration, in its support for tariffs, wrongly pointed to as a time of great livelihoods for the common American. What seems to have been forgotten by them is that the reaction to the Gilded Age was a battle by common Americans for a better life, marked with strikes and speeches, that eventually culminated in the Progressive Era.

One of the most famous reformers of the day, whose fight against the suffering of the masses led to these great strides in Progressivism, was Henry George. His words in opposition to tariffs give a direct understanding of how harmful they can be:

“It is only to those who, in addition to being protected from foreign competition by the Tariff, are also able to defend themselves from domestic competition by the possession of peculiar natural opportunities, patent rights or trade secrets, or who are able to organize combinations or trusts, that Protection can give any permanent advantage. Thus, in the last analysis, Protection can only benefit monopoly.

…

under the protective system, the favored few are permitted to collect the taxes for themselves in higher prices.”

The issues that make societies chime for tariffs and the making of all production domestic are either issues better fixed by other policies, or just outright self-inflicted. Speaking to the latter in particular, governments levy heavy taxes on the production and trade of goods and services, granting the effect of discouraging the work and investment needed to realize them; then, in the same breath, allow speculation and hoarding in resources which are necessary for production to occur yet are non-reproducible, stifling it further. These ailments which plague economies are ultimately unnecessary, and are only worsened by blaming access to foreign markets instead of domestic policy failures.

The Facade

People produce and trade goods and services to satisfy wants and needs, any tax levied on the act of doing so directly prevents individuals from satisfying themselves and others. Tariffs are perhaps the worst of them, shutting out the outside world where countries that can do a better job of producing a particular good or service are unable to give them to those countries not best suited for the task.

The would-be exporter and its people lose access to the returns of trade, the would-be importer and its people lose access to cheaper produced articles from abroad, as well as a semi-monopoly of big businesses that gain newfound power in the face of little to no foreign competition.

Broad tariffs are the strategy of a paper lion. They force all production and trade to occur within the borders of the nation, giving the facade of strength and self-reliance. But in reality, they deny opportunities and advantages to locals and the foreign lands they would trade with in a free society, withering and washing away the wealth and well-being that would make a nation and its population healthy and prosperous.

With tariffs now covered, we can now move on to the third leg of this trip in taxation taxonomy: payroll taxes

Leave a comment