If you opened this article, chances are you made use of a particularly special natural resource. It’s not one we can touch or even see, but outside of land might just be the natural resource we’re most acquainted with. Modern devices like laptops and phones make use of it for all digital communication across the internet. This resource, underrated in its impact on our lives, is the radio spectrum.

The radio spectrum is an invaluable, seeing use in every facet of our modern, digitized economy. Such a resource is vital to access, which is why there’s been an ongoing battle for it among actors ranging from major tech companies like Google and Amazon, to wireless service providers like AT&T and Verizon. To understand and quantify this, we need to understand where the spectrum comes from, how it’s been publicly handled before, and where it’s going.

Riding the Waves through History

Knowledge of the electromagnetic spectrum, which the radio spectrum forms a part of, has existed since the very turn of the 19th century, when German-British scientist Sir William Herschel successfully used a glass prism to discover the infrared light we see as colors in 1800. 87 years later, German scientist Heinrich Hertz successfully produced electromagnetic waves, particularly radio waves, in his laboratory; opening the gates for a new era of communication. For his achievement, the measurement for an electromagnetic wavelength’s frequency, the Hertz (Hz), was named after him.

Shortly after its inception, it became clear that the radio spectrum, being a natural resource prone to scarcity, would require regulation. The first attempt at regulation, which was ultimately ineffective, arrived in the form of the Radio Act of 1912. It was later replaced by a few more laws, culminating with the Communications Act of 1934 which created two new regulatory bodies for the spectrum: the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). For the purposes of this section, we’ll be looking at the policies of the FCC, and how they ventured into the potential of capturing the spectrum’s value.

For the first 60 years of its history, the FCC handed out licenses to use portions of the radio spectrum. Licensed spectrum allows exclusive access to naturally-occurring waves, eliminating the possibility of interference from outside parties without legal repercussions. Licenses were originally given out on a comparative hearing, and later was decided through a lottery. But a major change took place in 1993 that allowed the FCC to recoup some of the spectrum’s value for public use, while allocating it on a market basis; they were granted the power to auction off frequencies.

The FCC held its first auction in 1994, for the 901-941 megahertz (MHz) band of the radio spectrum, with total bids crossing over 600 million dollars. Since then, crossing up to early 2022, the FCC has raised about 233 billion dollars over the span of 28 years, an average of 8.32 billion dollars a year.

However, the FCC has started down another path of making portions of the spectrum free for public use without a license, aptly called unlicensed spectrum. Unlicensed spectrum’s freedom comes at the cost of potential interference from other spectrum users without any legal defense, though advancements in tech have allowed the spectrum to be crowded more without problems.

This all points to a need to balance the desires of the public good and the private users of the spectrum. Thankfully, as with other natural resources, there is a way we can balance private and public needs, more on that later.

What’s clear is that the spectrum is a desirable, non-reproducible natural resource with a finite bandwidth. Its value thus forms a part of the economic “land” that Henry George and his followers have been in the hunt to recoup in lieu of taxing work and investment. With the boom in technology that makes use of it, the question that remains is: just how valuable is the spectrum?

The Value of the Waves

Unfortunately, there doesn’t exist a comprehensive estimate as to the spectrum’s value, but some estimate of how much spectrum was given away can point us in the right direction. As far back as 2003, spectrum experts Michael Calabrese and J.H. Snider estimated that the value of commercial access to the invisible waves powering our future totaled an astounding 750 billion dollars, likely as a capitalized selling price. Remember, this was before the rise of the smartphone and other advancements that give rise to the far greater inter-connectivity we see in the world today.

While great for understanding the early days of the internet, these numbers don’t do modern spectrum use justice. We can get a much more recent estimate by looking at the value of what is perhaps the spectrum’s greatest and most well-known use, Wi-Fi.

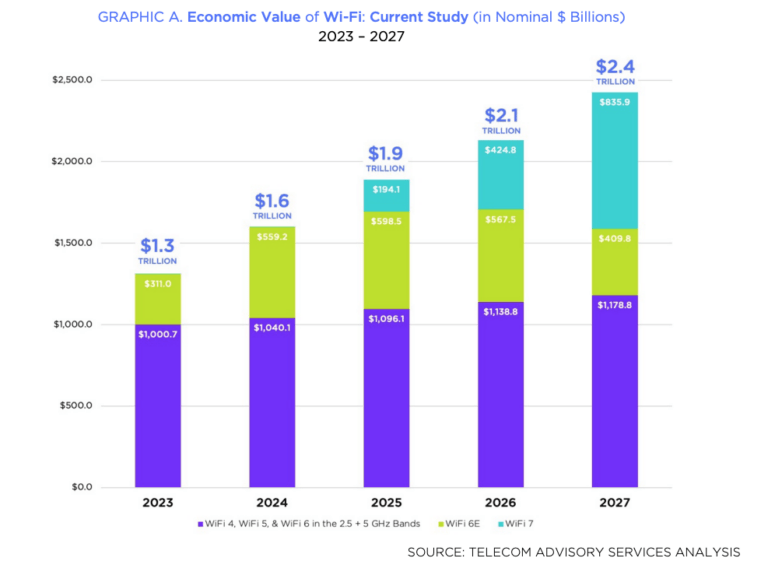

As we can see, the total value of Wi-Fi’s effect on the whole economy in 2025 sits at around 2 trillion dollars, potentially cracking 2.4 trillion by 2027 as more radio spectrum is released for use without licensing. And remember, Wi-Fi doesn’t take up all the radio spectrum, much of which is still held under licenses auctioned off to TV and Radio broadcasters through lobbying and political pleading, another issue with the spectrum’s use covered by J.H. Snider.

This isn’t to say all of Wi-Fi’s value is value inherent to the radio spectrum, but it does show just how crucial the radio spectrum is in our everyday lives, and its potential magnitude. The value of the spectrum as decided by society is crucial, as it gives us a way to compensate those excluded when a particular frequency is taken up for use.

Balancing Private and Public Needs

“As with all these “exotic” resources, there quickly emerge three camps. The first wants to collect rent publicly. The second dismisses distributive equity and focuses on framing up existing tenure rights. The third camp is solely concerned with asserting the public right, regardless of efficiency. The beauty of taxing rent, of course, is to achieve and harmonize the (professed) goals of the second and third camps. It would have prevailed long since, were the second and third camps more aware and respectful of the validity and sustained power of each others’ half-share of truth.”

These were the words written by Mason Gaffney surrounding the management of the electromagnetic spectrum back in 1982. Over a decade before the FCC began its auctions. Gaffney, as do other Georgists, believe that the best way to combine the needs of the public and private users of the spectrum is to recoup its value on behalf of the public, while leaving any use of the spectrum for work or investment untaxed.

How would this look? It’s hard to say. One particular proposal pushed forward by Georgist professor Nicolaus Tideman is to have a form of options market for particular frequencies, where bids are solicited annually. Assessments for both licensed and unlicensed spectrum are another possibility, as proven by the previous writings of Calabrese and Snider. There exists multiple possible paths for balancing the needs of the public and private users by collecting the value of the spectrum.

Despite its uniqueness as being an ethereal natural resource beyond our sense of touch, the spectrum falls into the same category of resource as all the other sources of economic rent discussed in this series. In the words of the late Fred Foldvary:

“The 21st century will be a world of virtual and global commerce, and speed-of-light transmissions. Money as well as many goods will consist of electrons. Taxing electrons will be expensive, futile, and counterproductive. But space, both in real-estate and in the radio spectrum, and natural material resources such as oil, water, and minerals, can be tapped for revenue without hurting production or making it run away. Land is fixed and immobile.”

Leave a comment