How Property Taxes Confuse Us into Making Everything Worse

Editor’s note: this article was originally published by the author on The Georgist Toolkit Substack.

Property taxes include land value taxes. If property taxes can be passed off to tenants/consumers — seemingly like all other taxes can be passed off to tenants/consumers — why would land value taxes be any different?

Contents:

- Skill Issue: Evolving the (Typical) Georgist Answer

- Answer: The Shortest Long Version

Skill Issue: Evolving the (Typical) Georgist Answer

Most people understand the economic incidence1 of taxes experientially, but not the mechanism behind how “passing off increases in costs” is actually accomplished.

(If you are a fan of LVT, but don’t care about Georgism much, skip to the next part.)

Modern-day Georgists may be able to get away with surface-level approaches when discussing this subject with an audience that doesn’t actually plan on giving it much more thought and will accept any explanation given. It is the same argument which Henry George used as his starting point (after providing background/context on why answering this question is important, stating his case/thesis, and appealing to the authority of John Stuart Mill) in his article on “Why the Landowner cannot Shift the Tax on Land Values” in The Standard2, so it’s a bit of a (truncated) tradition in our circles. This argument typically takes the following form:

Landlords are already charging as much as they possibly can. What is preventing them from increasing rent now?

It’s sort of a rhetorical question, so it doesn’t really explain anything. The effect of this is to either:

- make the good faith inquirer feel more self-conscious about their lack of economic knowledge, or

- make the bad faith inquirer feel superior for assuming that a lack of articulation infers that there is no good argument to be made.

The typical reaction to such a Georgist comment is to point out that:

- what this implies is that prices could never change, period, (which is obviously false,) and

- not everyone is always charging as much as they possibly can (e.g. “mom and pop” landlords who do not pay attention to rent increases in nearby comparable properties).

This flubs an opening and puts Georgists on the back foot. Not great.

We need to do a much better job at explaining why land is different.

Land is fixed in supply.

While true, this, by itself, doesn’t exactly help them connect the dots. This might come through for a Georgist speaking to another Georgist, but just about any other audience is either going to:

- try to come up with edge case scenarios where more land is being “created” (moving piles of sand around, a.k.a. land reclamation projects), or

- start in on some inarticulate version of why the effective (on-market) supply of land is not fixed (which is true) and deliberately ignoring our point about how the total supply of land being fixed (effective supply plus latent supply, or, on-market supply plus off-market supply) is the game-changer.

Another fairly succinct approach which is slightly more explanatory than simply pointing out that land is fixed in supply, but still relies heavily on audience familiarity with the subject of taxation or microeconomics:

A tax on land neither decreases supply nor increases demand.

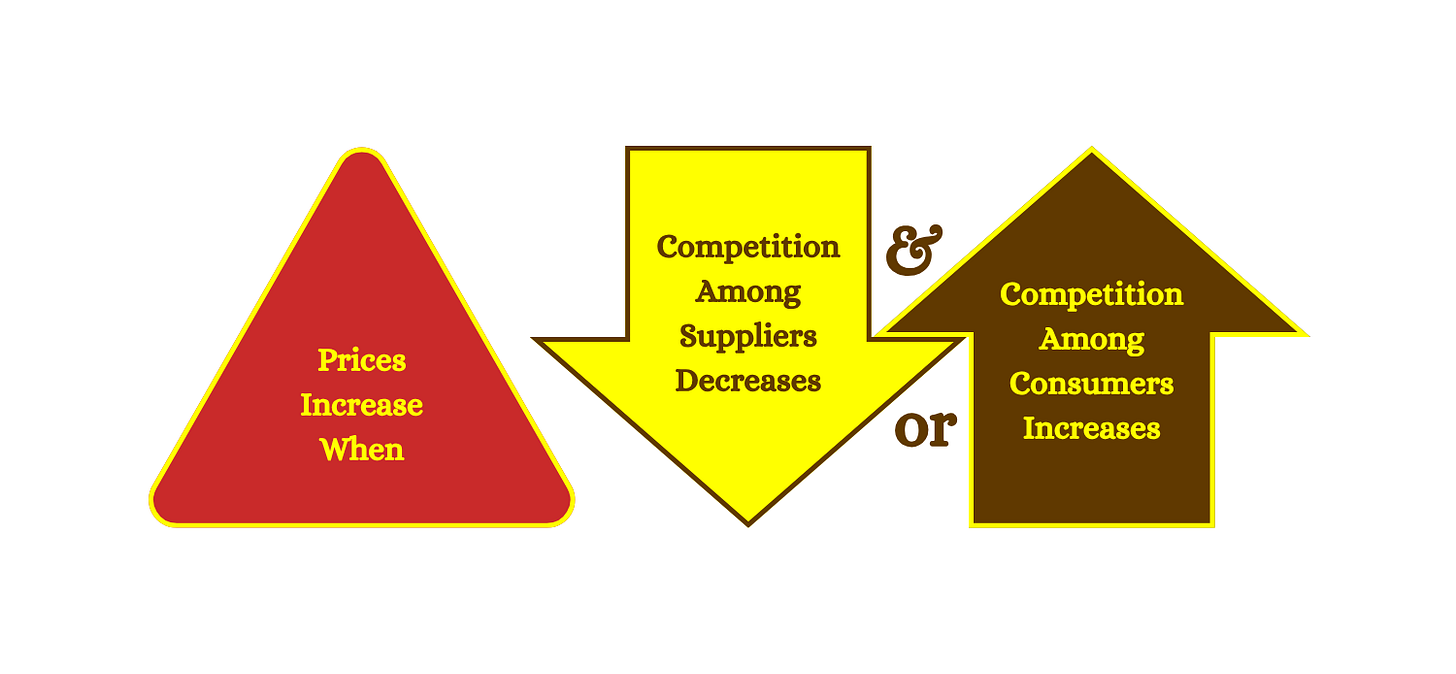

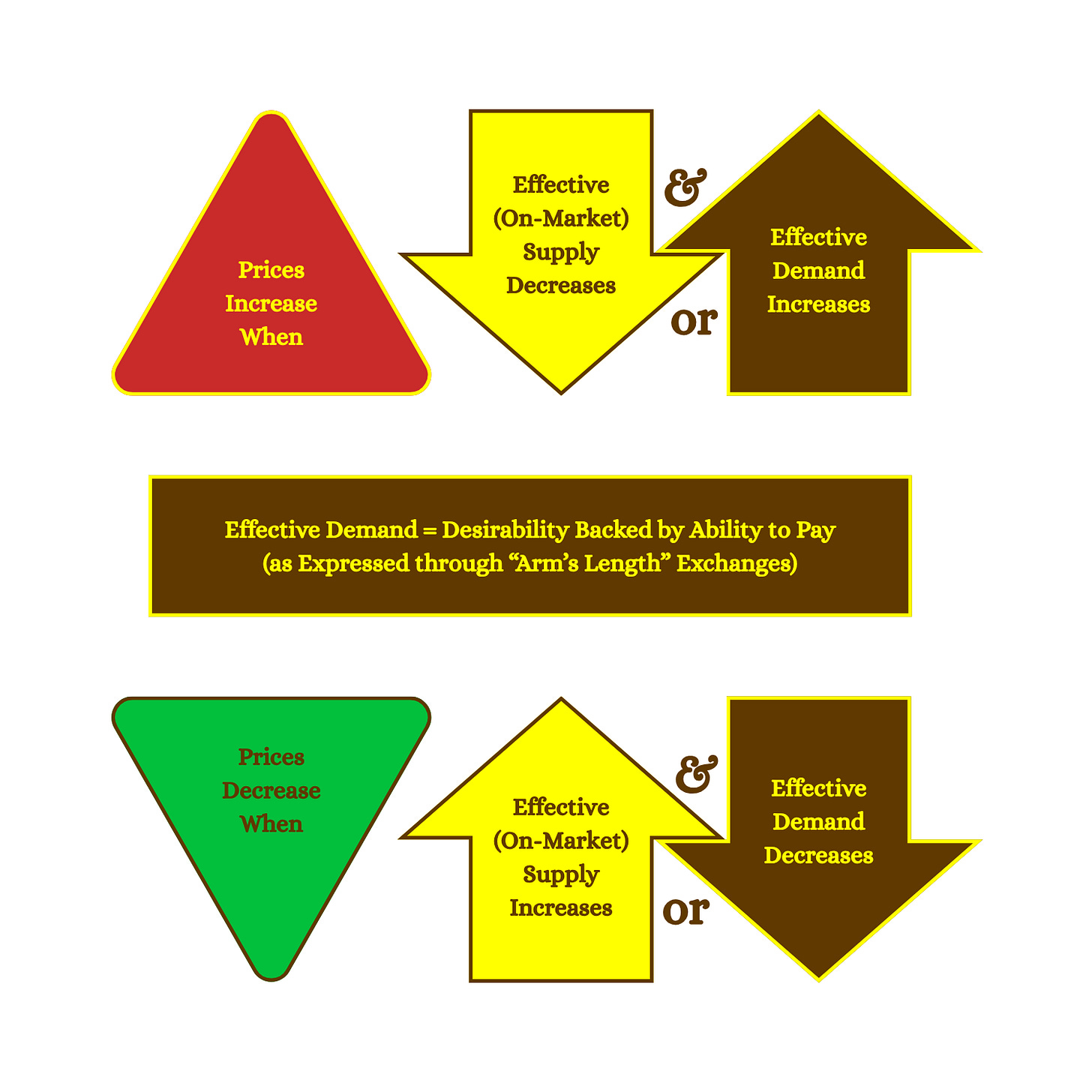

I actually kind of like this one because it is very elegant. The two things which drive prices up are (1) increased competition among consumers or (2) decreased competition among suppliers3 — and imposing a value tax on land triggers neither condition. However, it still relies heavily on the audience to connect a lot of unspoken dots for themselves.

Land is not produced, so a land value tax does not result in things-which-maybe-should’ve-been-produced to stop being produced. And on the demand side, consumers aren’t getting more money. Perhaps an economist who has never thought too deeply about land would read this and instantly be overcome with profound insight, but probably not the lay audience.

If such approaches were to be continued, I would soften the framing a bit to be more of a guided-discovery process than a challenge. For example:

Great question! Let’s walk through the mechanics of that by starting with what you know. If we assume that landlords are already charging as much as they possibly can, what is preventing them from increasing rent now?

It’s basically the same question, but framed as more of an invitation to discuss and think instead of a way of shutting down the opposition. As they say in the sales world, we want to get good at “handling objections.” We’re essentially acknowledging their interest (“Great question!”), imagining that we’re on a journey together now on the same team instead of competing on opposite sides of a debate (“Let’s walk through […]”), and passing the ball back to them when we stop ourselves short of making assumptions about their level of understanding … when we ask a foundational question and see how they respond to it before moving forward.

After all, “a person convinced against their will is of the same opinion still.”

If we’ve successfully engaged the skeptic, are we prepared to follow through with the discussion? When it comes to commodities, we could make the same assumption — that producers and sellers are already charging as much as they can, so what is preventing them from increasing the price now? Clearly, they are able to pass off taxes somehow after a tax (or other cost increase) is implemented, even if the skeptic isn’t able to fully articulate how that is achieved.

Help them solve the puzzle!

Answer: The Shortest Long Version

Before I launch into the various implications of a shift from taxes on production to taxes on land value, here’s a version which I think connects all the essential dots. It isn’t too short, but it also leaves plenty of relevant avenues unexplored, which makes it an excellent conversation starter.

- Tax Incidence & Evidence: When most people talk about taxes being “passed on” to the consumer, they generally mean that when the tax increases, the price the consumer must pay also increases. But when it comes to increasing land value taxes, studies show that sale prices decrease.4 The evidence shows that not only are land owners not able to pass on the tax, but that land owners absorb the tax fully. Why might this be the case?

- Same in the Short-Run: When costs increase for the suppliers, suppliers may try to increase prices, but it is ultimately how the consumers respond to this which will determine whether or not those higher prices stick. Consumers will not tolerate exploitative prices if they have viable alternatives (substitutes) available. Healthy competition among suppliers keeps prices down. However, when costs (taxes, etc.) increase for the suppliers, the suppliers operating on thin margins are no longer profitable. This is true for goods as well as land. Let’s talk about how they diverge.

- Standard Impact with Produced Goods: When suppliers of produced goods abandon their (now not-profitable) businesses, less is produced in aggregate. The producers which remain are not only (1) already the ones charging higher prices, but also (2) now potentially have more customers from the previously-met now-unmet demand. The customers with unmet demand can (A) try to find substitute goods, (B) pay the higher prices from the remaining suppliers, or (C) stop buying the product. Increased competition among consumers (those remaining with the ability to pay5) drives prices up.

- Different Impact with Land: However, when suppliers of land abandon their land, the government recycles it back into the market (provided they don’t leave real estate in their land banks for long), which increases aggregate supply available on the market. Consumers will not tolerate exploitative prices if they have viable alternatives (substitutes) available. Increased competition among suppliers drives prices down. In contrast, under status quo, keeping land cheap to hold encourages supply to be held off-market and unavailable to consumers. Increased competition among consumers drives prices up.

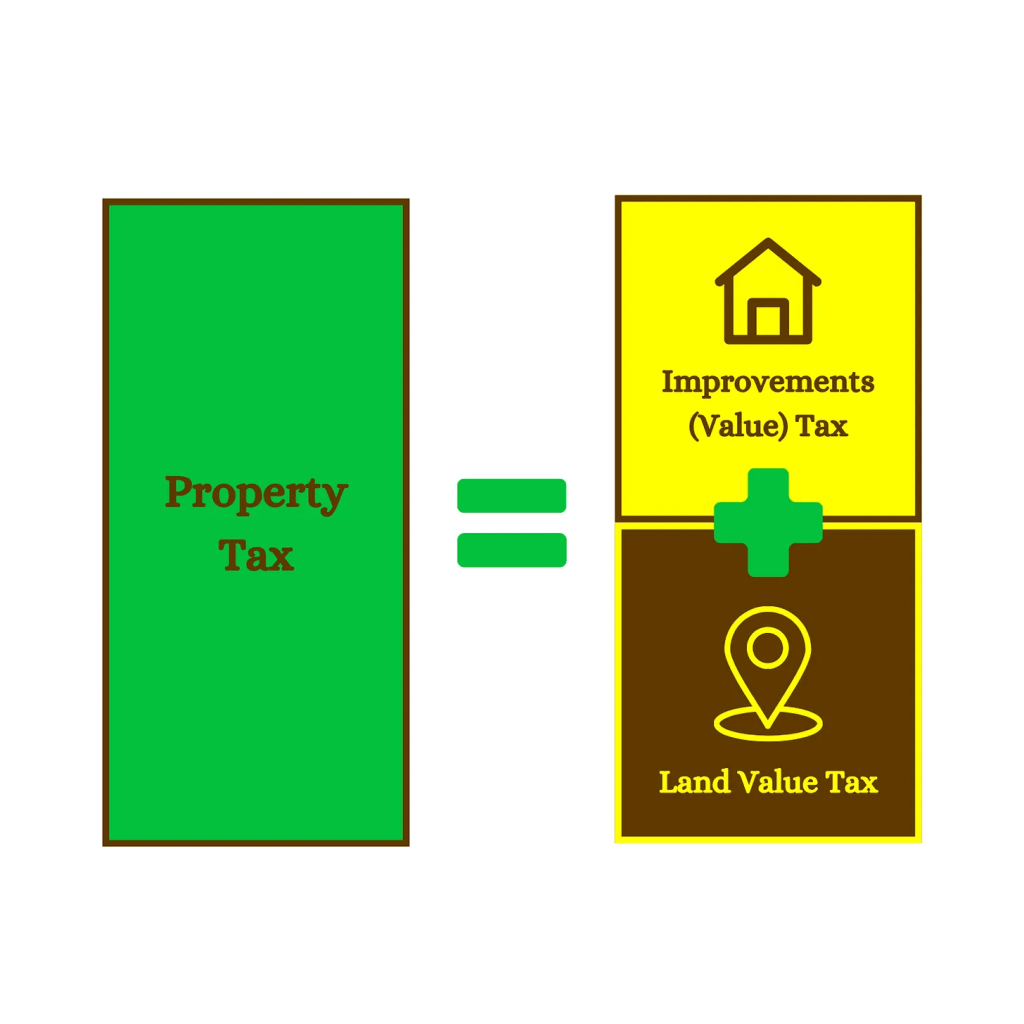

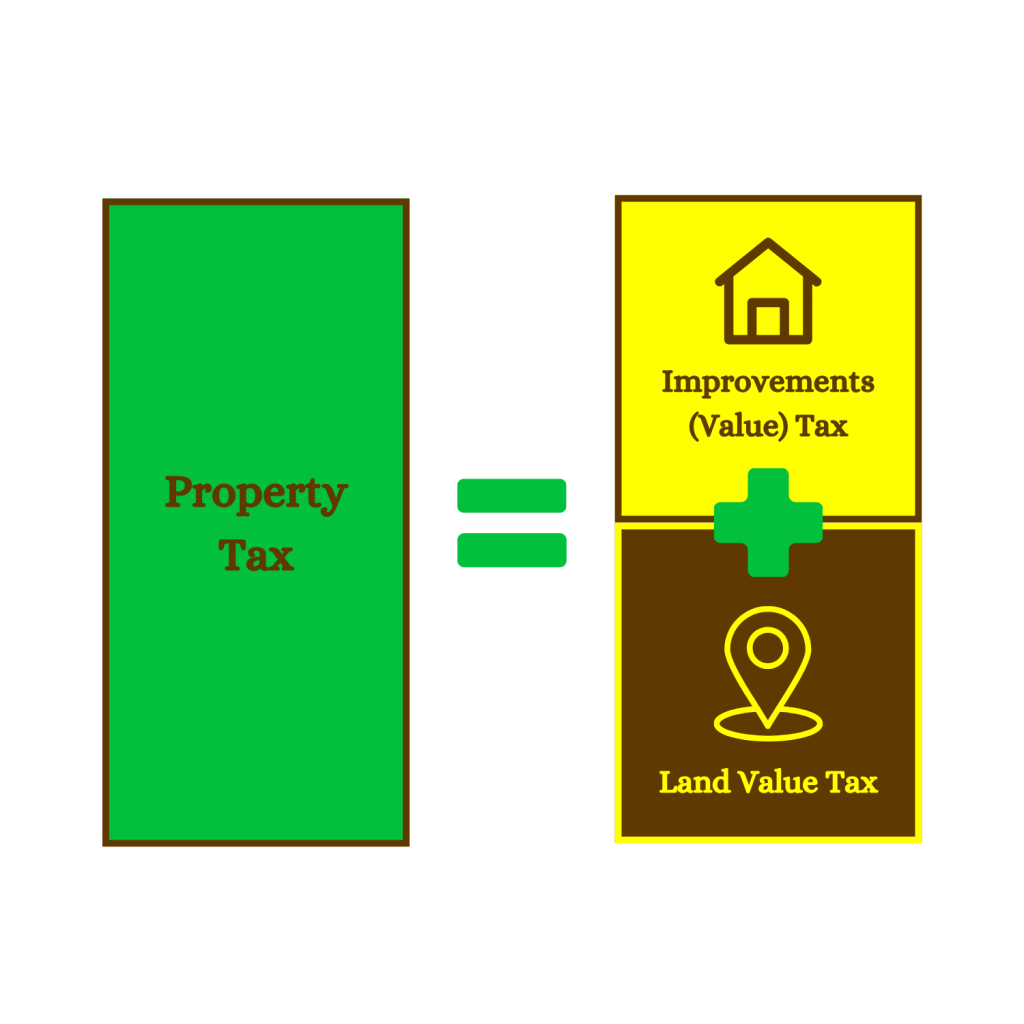

- Mixed Impact with Property (Improvements + Land): Contrast this with a traditional property tax which includes a tax on improvements (like housing, which is produced) and you can see why increases in property taxes tend to be passed on to consumers when the consumers for those particular types of improvements have few alternatives.

I think a reasonable person would be able to follow this without ever having seen a supply-and-demand graph, heard of elasticity, understand dead-weight loss6, or know what a Harberger’s triangle7 is (tax wedge8 or George’s wedge9).

Want to know more?

We have a thriving community of people who would love to answer all your questions about Land Value Tax, Universal Building (Tax) Exemption, and ways to mitigate any other kind of monopolistic privilege you can think of — check us out!

Georgists proudly welcome you!

Answer your LVT questions on Discord!

Thank you for reading The Georgist Toolkit. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Want more tools in your Georgist Toolkit? Get them delivered to your inbox as soon as they are released!

Legal incidence identifies who is responsible for paying a tax while economic incidence identifies who bears the cost of tax—in the form of higher prices for consumers, lower wages for workers, or lower returns for shareholders.

(Emphasis mine.)

Tax Incidence: https://taxfoundation.org/taxedu/glossary/tax-incidence/

To suppose, in fact, that such a tax could be thrown by landowners upon tenants is to suppose that the owners of land do not now get for their land all it will bring; is to suppose that, whenever they want to, they can put up prices as they please.

This is, of course, absurd. There could be no limit whatever to prices did the fixing of them rest entirely with the seller. To the price which will be given and received for anything, two wants or wills must concur – the want or the will of the buyer, and the want or will of the seller. The one wants to give as little as he can, the other to get as much as he can, and the point at which the exchange will take place is the point where these two desires come to a balance or effect a compromise. In other words, price is determined by the equation of supply and demand. And, evidently, taxation cannot affect price unless it affects the relative power of one or other of the elements of this equation.

Henry George, “Why the Landowner Cannot Shift the Tax on Land Values” (1887):

https://www.cooperative-individualism.org/george-henry_why-the-landowner-cannot-shift-the-tax-on-land-values-1887.htm

&

https://bibliotek1.dk/english/by-henry-george/articles-and-speeches/why-the-landowner-cannot-shift-the-tax-on-land-value

This is the digestible version. I suspect that we could imagine having a single supplier (true monopoly) which increases supply and price decreases, so it is more technically correct to say that effective supply decreasing causes price to increase, etc.

The approach adopted in this paper is a before, during, and after treatment setup due to the likely gradual formation of expectations of future tax rates described in section 2. This requires data on property prices for single family homes prior to the implementation of the reform as well as prior to the announcement of the reform. Single family homes sold from 2001 and up to the announcement in the second quarter of 2004 are used as a pre-treatment group. Single family homes sold between the third quarter of 2004 and the implementation of the reform on January 1, 2007 constitutes a during treatment group. The mergers and new tax rates were decided and announced during this period. Lastly the after treatment group consists of houses sold during 2007 and 2008.

The results demonstrate a clear effect on sales prices of the observed changes in land tax rates. Furthermore, the magnitude of the changes implies full capitalization of the present value of the change in future tax payments for a discount rate of 2.3 per cent, which is within the range of reasonable discount rates for households during the period in question. The analysis consequently supports the hypothesis that perceived permanent land tax changes should be capitalized fully into the price of land and property.

The result supports the view that a tax on the value of all land like the existing Danish land tax does not distort economic decisions as it does not affect the user cost of land and consequently the relevant relative prices.

[…] the full incidence of a permanent land tax change lies on the owner at the time of the (announcement of the) tax change; future owners, even though they officially pay the recurrent taxes, are not affected as they are fully compensated via a corresponding change in the acquisition price of the asset.

In summary, a 3.4 per mille points increase in land tax from the time of “reliable announcement” in June 2004 to the time of implementation in January 2007 led to a 2.3 per cent decrease in sale prices and mortgage bonds, so increases to LVT are not being passed off to tenants in the form of higher rents.

Discount rates found in similar studies, as cited in the paper:

- 2.3-2.9% Borge and Rattsø (2014)

- 2.6% Giglio, Maggiori, and Stroebel (2015)

- 2-3% Do and Sirmans (1994)

Høj, Jørgensen & Schou, “Land Taxes and Housing Prices” (2017),

København : De Økonomiske Råds Sekretariatet: http://hdl.handle.net/11159/1082

alt: https://savearchive.zbw.eu/bitstream/11159/1082/1/arbejdspapir_land_tax.pdf

By themselves, utility and scarcity confer no value on land. User desire backed up by the ability to pay value must also exist in order to constitute effective demand. The potential user must be able to participate in the market to satisfy their desire.

(Emphasis mine.)

Gwartney, Ted, “Estimating Land Values”, Understanding Economics, https://henrygeorge.org/ted.htm

[…] there are either goods being produced despite the cost of doing so being larger than the benefit, or additional goods are not being produced despite the fact that the benefits of their production would be larger than the costs. The deadweight loss is the net benefit that is missed out on. While losses to one entity often lead to gains for another, deadweight loss represents the loss that is not regained by anyone else.

In other words, this is the difference between our productive capacity and our realized productive output due to allocative inefficiencies. Georgism focuses on the systemic inefficiencies enabled by poorly devised government policies.

Deadweight Loss: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deadweight_loss

[…] the deadweight loss created by a government’s failure to intervene in a market with externalities.

Harberger’s Triangle: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deadweight_loss#Harberger’s_triangle

Tax Wedge: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tax_wedge

The new forces, elevating in their nature though they be, do not act upon the social fabric from underneath, as was for a long time hoped and believed, but strike it at a point intermediate between top and bottom. It is as though an immense wedge were being forced, not underneath society, but through society. Those who are above the point of separation are elevated, but those who are below are crushed down.

(Emphasis mine.)

George, Henry, Progress and Poverty (1879)

Leave a comment