This article is part 1 of a mini-series on The Daily Renter dedicated to talking about the many sources of economic rent other than the big one, land. For our first part, we have a particularly relevant one given recent booms in technological prowess, Intellectual Property.

Introduction

I recently wrote an article that went into depth about how both privatized economic rent and taxes on production are forms of theft in their own right, and why we should remove the latter in place of taxing the former.

For those who don’t know, I defined economic rent as the income of a resource which is non-reproducible; and as a part of that article, I briefly listed an array of sources of economic rent (including but not limited to that itself) that Georgists across history have taken time to focus on and criticize being turned into private profits.

One of those sources was Intellectual Property, which will be the focus for our first edition. But before we can delve into the Georgist take on Intellectual Property, we need to understand why Georgists have such a problem with IP.

Why IP, and Which Ones Do We Focus On?

First, we need to clear the air on what the original purpose of Intellectual Property is. Intellectual Property is essentially a legal privilege designed to reward an innovator by making their specific innovation non-reproducible by anyone else (with the exception of trade secrets). The purpose of this is to allow individuals to feel far safer when innovating, as they know they’ll be recognized and rewarded for it by knowing the legal system will have their backs.

As it relates to Georgism, this is fine for trademarks, as branding is a lot more fine-tuned and specific to individual companies or entities and is a good way to track what really belongs to them, so I won’t be talking about them. Trade secrets also won’t be a focal point, as the innovation covered under a trade secret can be reproduced by others if they independently find said innovation themselves.

Indeed, the two specific forms of IP that’ll be the focal point of this article are patents and copyrights.

As we already established, copyrights and patents exist to reward and recognize innovators by making their innovation non-reproducible. This is already risky, as it effectively grants IP owners to extract economic rents by excluding others from the production process for that innovation.

If made too strong and left too unchecked, IP can go from being a reward for a beneficial discovery to being a roadblock on the eternal human path of innovation and progress. Unfortunately for us, the latter has already happened in many cases.

The Problems with Our Current Patents & Copyrights

Patents and Copyrights are so strong and so long lasting that they’ve served more as a way to gain market and rent-extracting power than as a way to reward innovation. Some absurd shows of IP’s power lie in the fact that Copyrights have a lifespan of the author’s life and 70 years after their death.

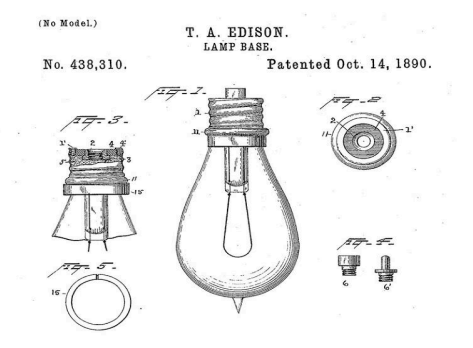

Patents don’t have this same length, lasting about 17 to 20 years, but the only thing required to keep that pure, unadulterated power of extracting rents off a non-reproducible innovation, is just a couple hundred dollars to a couple thousand dollars.

At the same time, taxes within our current system that target corporate incomes and gains, ones that would otherwise collect some IP rents, are often avoided, letting IP owners off the hook.

Under no circumstance do the fees paid by IP holders reflect the true cost put on society from making beneficial, potentially life-saving and life-changing innovations non-reproducible by anyone but the holder themselves. This, in turn, has led to innovations being withheld from society and turned into incredibly high profits and incredible amounts of market power.

A particularly potent example of the power granted by IP is Amazon’s one-click checkout patent, granted to them in 1997 and expiring 20 years later in 2017. For 20 years, nobody could reproduce the convenience compared to what Amazon provided. The one-click patent played a massive role in Amazon’s exponential growth to become the single largest online retailer on Earth. As of now, they hold over 30,000 patents, being granted 1,857 in 2023.

Indeed, Amazon isn’t the only large tech-based company using IP to base its power. Microsoft owns a huge 107,170 patents, while Samsung owns an absolutely monstrous 352,039 patents; and of course, as we know from the one-click patent example, it’s not just about how much IP you own, it’s about how valuable each individual IP is. With those two factors combined, the effects are clear.

The same problems caused by patents goes for copyrights as well. Large media corporations source much of their power in making specific characters and creative designs non-reproducible as well. Disney still owns the rights to Mickey Mouse almost a century after his creation, and Nintendo has used its copyrights over Smash Bros characters to strike down fan projects and videos.

Some of the largest and most monopolistic corporations in the world, especially in advanced industries like tech and medical care, have gotten and maintained their bearings through extensive ownership of patents and copyrights. Owning an armada of privileges which make powerful innovations non-reproducible, while paying little to nothing to keep them, is a fast track towards extensive rent-seeking.

Now with the entrance of artificial intelligence, a lot of questions surrounding the role and impact of patents and copyrights will rise. With the flaws of our current system, the potential issues brought on by monopolized AI technology could be troublesome without IP reform.

Some Things Never Change

That’s where Intellectual Property, and the problems with its economic rents, are at now. However, this problem has existed for a long time, so long in fact that Henry George himself criticized patents and excessive copyrights as far back as 1888.

Indeed, the original Single Tax movement was also tremendously critical of Intellectual Property even back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They suffered many of the same problems we suffer now, with Gilded Age monopolists using patents to deny reproducibility and add to the power of their monopolistic businesses.

One particularly special example of a Georgist criticism towards IP monopolies was from Tom L. Johnson. Once a Gilded Age monopolist who himself used patents, Johnson became a reformed and dedicated Georgist and eventual mayor of Cleveland. In the forward to his book My Story, Johnson calls the Georgist fight to oppose the menaces brought on by private profits in several sorts of non-reproducible resources and privileges, including in patents, as “The greatest movement in the world to-day.”

As can be seen, the Georgist criticism of unfettered and unchecked IP power has existed since the times of George himself. In line with this, several Georgists have offered their own remedies that deserve to be mentioned and discussed.

Solutions Among the Georgists

Every major problem requires a good solution. For the problems with land, Georgists near-universally call for taxing land rents. Same goes for the many other sources of economic rent, and patents & copyrights are no exception. Georgists collectively agree that, if a reward system is to exist, it should be limited in its timespan in order to prevent people from gaining a permanent advantage.

(Georgists who are fine with patents and copyrights’ existence agree they should last about 20 years, for example.)

From here though, differences begin to arise, as there are disagreements on how to best reward innovation and eliminate the problems brought by IP and its economic rents.

So, while there isn’t a concrete answer, there are different proposals amongst the community that can provide some view of a theoretical Georgist IP system.

Two major examples include:

- Replacing IP with a prize system (to varying extents): The first major proposal is one where the exclusivity of IP is replaced with prizes. Rather than using economic rents, a direct subsidy is given to the innovator as the main mode of payment and reward. Perhaps the most famous advocate for this system is Joseph Stiglitz (who himself supports the philosophy behind Georgism). The extent to which this is done depends on the Georgist, but the hope is to use the subsidy as a replacement for economic rent.

- Taxing IP itself: Another major Georgist proposal for dealing with rent-seeking on IP involves working within the system of IP itself, by taxing its ownership according to its value. The way this tax would work can vary, just like the aforementioned prize system. For example, some have called for using a Harberger tax while others have called for using auctions of the IP themselves, and then taxing whatever value auctioned IPs are set at. Other variations include how to set the tax rate, like deciding if it should increase or stay flat, and at what rate it should increase if we decide to go that route.

These are just a few of the examples of how a Georgist solution for our current innovation-reward system might look, and there are other proposals not mentioned here which might be of interest as well. Ultimately though, there is something all Georgists can agree upon.

Conclusion

Regardless of what solution a Georgist might propose for dealing with IP, the common reasoning is the same. The economic rents of IP that flow from making production/trade with a specific innovation non-reproducible shouldn’t be left unfettered to whoever owns the IP.

Whether that comes through taxing IP rents directly or replacing IP with another reward system that keeps innovations reproducible, our current system has always been criticized by the Georgists owing to the power it grants over the rest of society.

So, no matter how much technology has improved or progressed since George’s time, and how much it may do so in the future, unless we reform our IP system to be focused more on rewarding and using an innovation for production, instead of rent-seeking off keeping an innovation non-reproducible, the problems of IP will always remain and demand reform.

Leave a reply to The Agricultural Squeeze: How our Working Farmers are Being Pushed into Poverty – The Daily Renter Cancel reply